Make no mistake: this is a beautiful film, beautiful for its modesty, its respectfulness, its clarity and piquancy of image both sundraped and nocturnal. Rendez-Vous de Juillet is a young film about young characters. It was not made by a young man, but it keeps its spirit and feeling of youthfulness because, like the young, it believes simply existing is enough to justify itself and to demonstrate its worth. It is not wrong in this belief.

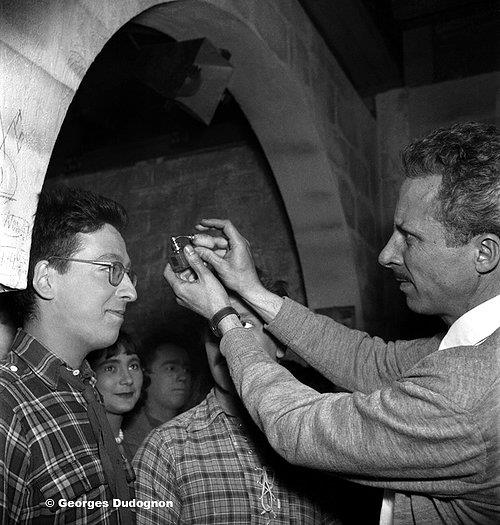

Daniel Gelin is Lucien, an anthropology student in post-war Paris struggling to finance a documentary film to be shot in Africa, Maurice Ronet’s Roger has recently completed his schooling in cinematography but is frustrated by the lack of opportunity in the film industry and plays Jazz trumpet to pass the time. Brigette Auber is Therese, an aspiring but untalented actress who bumps up against the sleaziness of the adult showbusiness establishment, and Nicole Courcel is Christine, an actress trying to make her way through on skill alone. Pierre Taubard is Pierrot, the son of a butcher, the clown prince who is also a promising actor and drives a combined boat-car painted like a shark. They are surrounded by a like-minded network of friends stuck in mundane, unstimulating employment while they await their big chance- the chance that Lucien’s documentary might be able to provide.

The characters in Rendez-Vous De Juillet dream and their dreams paradoxically feel real, balanced between the optimism of childhood and the distrust and compromise of adulthood (or, as Godard would have it, the monstres). In the moment, they live in a constant, if sometimes sublimated, frustration at the slowness of the actualisation of their imaginings. (The actors themselves are balanced between movie-star handsomeness and an adolescent gawkiness that corresponds perfectly with their character’s lives of delayed actualisation and longing.) All of this is enough to remind us that Becker was the first true heir to Renoir. The former assistant director understood his mentor (and Claude and Marguerite Renoir are here too, helping Becker as he becomes a master in his own right), and as a result we are sympathetic even to the characters some film-makers would only pour scorn upon because Becker, like Renoir, displays to us their confusion, their fear, every bit of the motivation that leads them to take the actions they do. For once, the young are not simply mocked; their lives are presented as their lives, and even in the Jazz clubs so detested and feared by their parents’ generation we see how they maintain their essential element of purity. And the actors themselves are balanced between movie-star handsomeness and an adolescent gawkiness that corresponds perfectly with their character’s lives of delayed actualisation and longing.

But Rendez-Vous de Juillet also has something in common with certain cultural products of the following decade, other artefacts of immediate post-war optimism and reawakening (or redreaming?). As in Colin MacInnes’ novel Absolute Beginners we see the new teenagers and twentysomethings trying to build their own world, enveloping those of all backgrounds into a sort of stylish, creative, classless semi-utopia (after all, see how easily the children of factory owners and butchers mingle and aspire together in his film). Of course this mindset is not without its anger and contempt towards those who came before, so elegantly summed up by Daniel Gelin’s Lucien, the aspiring explorer/documentary-maker, when he warns his friends who begin to show their reluctance to engage in his film-making expedition that they could end up like their parents who “found their slot… you’ll fade away like them, living safe little lives with no risk”. In these years the young seemed ready to throw off the suffocating side-effects of the search for comfort in life undertaken by those old enough to truly experience the war. Selfish? Perhaps. But in these works we begin to feel a sense of necessity, a response that meant that the streets were once again truly alive, ready and dancing to a new tune. This dream may today be near-forgotten, either temporarily or definitively, unification and common purpose destroyed by economic uncertainty and globalised neo-liberalism (not to mention the latest rise of fascism), but in Rendez-Vous de Juillet it is a dream in first bloom. The characters may be frustrated and a little lost when the film begins (even in these days there were not enough films being made for these newbies to be granted their first opportunities), but they also delight in their lack of conformity and their misfit status. And when the moment comes to choose between mundane security and adventure they, of course, finally decide on the latter. The camera responds in turn, delighting in being around these little human bursts of reinvigoration, and it follows their joys and despairs with an easy, loving grace and the occasional giddiness. Almost evert shot in the film, sharp and vibrating with life, has the freshness of the first drops of spring rain on the face.

One wonders why more young film-makers who are struggling do not take something from Becker’s approach? Rendez-Vous de Juillet would have a significant impact upon the Nouvelle Vague directors who realised the possibility and charm of simply shooting their friends, or the new youngsters replacing the older dreamers, as they drifted through their contemporary lives and world, letting meaning unravel in their wake. Most significantly we see the influence of Becker’s film in Rozier’s and Rohmer’s early work, and more scientific, analytic versions of the same in certain Godard and Chabrol films. And twenty years before Becker, we saw the German debutants of People on Sunday setting a kind of standard. But since these New Waves of the 1960’s we have been met with efforts that so often fall into the trap of contrivance, of posturing, even of a sort of self-worship that forgets the lessons of predecessors, i.e. that the emphasis should lay upon simplicity, modesty and the ability to step outside oneself or a generation and truly look at it, truly attempt to track it’s course and understand precisely from where it is from, what it is doing right now and where it is going. Becker (like the Germans and the New Wavers) was able to achieve this, and as a result his film feels forever young while some of his successors survive only with the dust of the museum upon their shoulders.

Remarkably Rendez-Vous de Juillet is almost two hours long, but it feels as sharp and concise as a Maupassant short story, and it glides by with the sweetness of the warmest daydream.